Capital gains occur when securities are sold at a higher value than their purchase price, reflecting growth in your portfolio. While this is a positive sign, it also comes with a tax bill. For this article, I attempted to solve for the minimum amount of capital gains a balanced portfolio will generate each year. The result could be used in financial plans, supporting assumptions for future portfolio tax. It could also serve as a potential benchmark for identifying accounts with unusually high levels of tax, and help diagnose and treat potential issues.

Setting it up: I ran hundreds of years’ worth of simulations for a moderately aggressive investment account with my own, extremely simplified assumptions of return and volatility, which are noted in the footnotes. I also factored in trading once per year, to re-balance the account back to its initial stock/bond split. The result tells me what percent of the account is subject to capital gains tax each year.

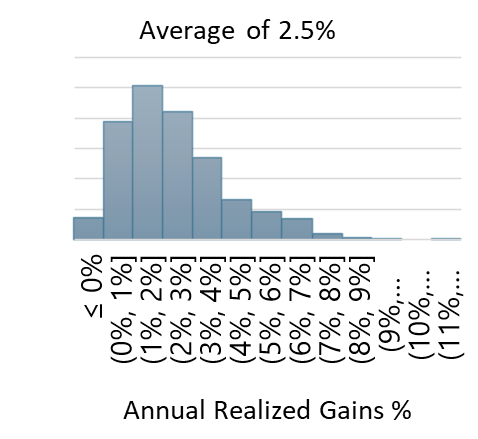

Result:

- The amount of realized gains per year on average was about 2.5%. This was a bit higher than my initial guess. In other words, on a $5M account you can expect roughly $125k in realized gains per year. (multiply that by your tax rate to get roughly $30-40k in actual taxes owed). Note, the account grows more than 2.5% annually. I am just talking about the realized gains from buying/selling.

Other Results:

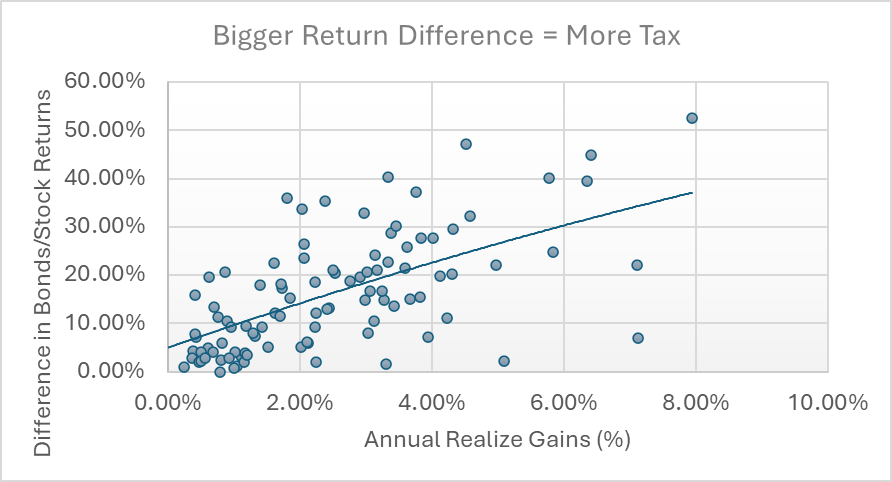

2) Big return differences (not combined portfolio return) between securities cause abnormally high tax years. In other words, stock being up and bonds being down triggers more portfolio trades than when both stocks and bonds are up.

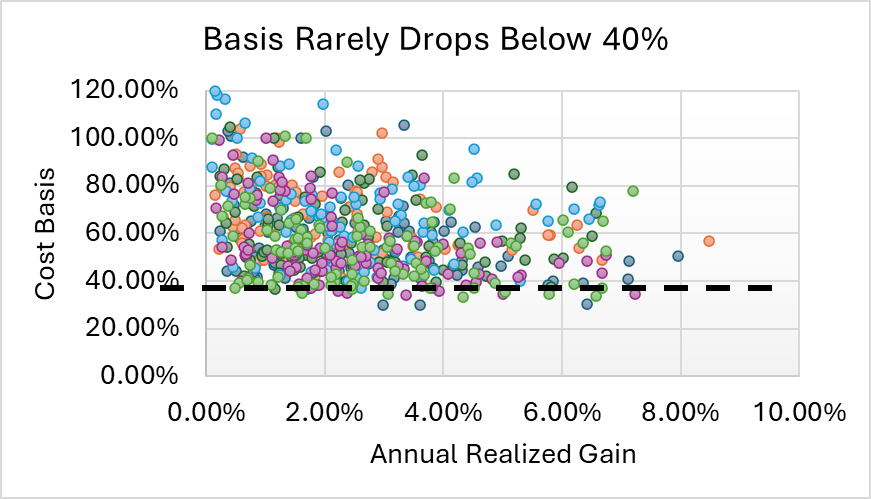

3) Unexpectedly, the cost basis of the accounts seemed to find a floor at 40%. In other words, annual rebalancing keeps taxes from getting too out of hand. Also, there is only a weak relationship between a mature account and high tax. Accounts with big unrealized gains do not necessitate big taxes.

Conclusions:

The benchmark of 2.5% annual realized gains could be useful for projecting future tax expense, so long as the accounts in question follow the assumptions I used, are broadly invested, and geared towards stock and bond market-based returns. Accounts straying from this 2.5% figure should be unique in other ways, such as a different investment objective, different strategies, or tax treatment. Factoring taxes into portfolio returns is uncommon but extremely valuable.

Assumptions: Bonds 4% return; 10% stdv; 30% allocation. US Stock 7% return; 19% stdv; 49% allocation. International Stock 7.5% return; 21% stdv; 14% allocation. Emerging Stock 8% return; 23% stdv; 7% allocation. Starting portfolio: $1M, rebalanced annually. Correlations of returns not taken into account.

Disclaimer

All calculations within are performed from scratch and, while diligent efforts are made to ensure accuracy, may contain unaudited errors. The content provided is for informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice, an offer, or a solicitation to buy or sell any financial instruments. Readers should consult with a qualified financial advisor for personalized advice tailored to their individual circumstances. All investments are subject to a risk of loss. Diversification and strategic asset allocation do not assure profit or protect against loss in declining markets. These materials do not take into consideration your personal circumstances, financial or otherwise, and cannot be applied directly to your situation.

Leave a comment